Ranjit Singh Malhi said the government’s move to make history a compulsory subject for Malaysian students in all education streams – including international, religious and UEC-linked schools – is “crucial” for the country.

He said the subject, as taught in schools, must accurately reflect the contributions of all communities in nation-building, with special recognition given to the central role played by the Malays in shaping the nation’s political and social landscape.

“History taught in schools should be inclusive, with reasonable focus on the Malays, but not at the expense of marginalising other ethnic groups.

“If taught truthfully and inclusively, history can unite us. It creates a sense of pride and belonging,” he told FMT.

Ranjit welcomed the government’s decision to establish a national historians council, calling it a positive step towards reform.

“To be fair to the Madani government, they have set up a national historians council, and they have stated that they want our history to be inclusive. That is the right direction, but we need to put it into practice,” he said.

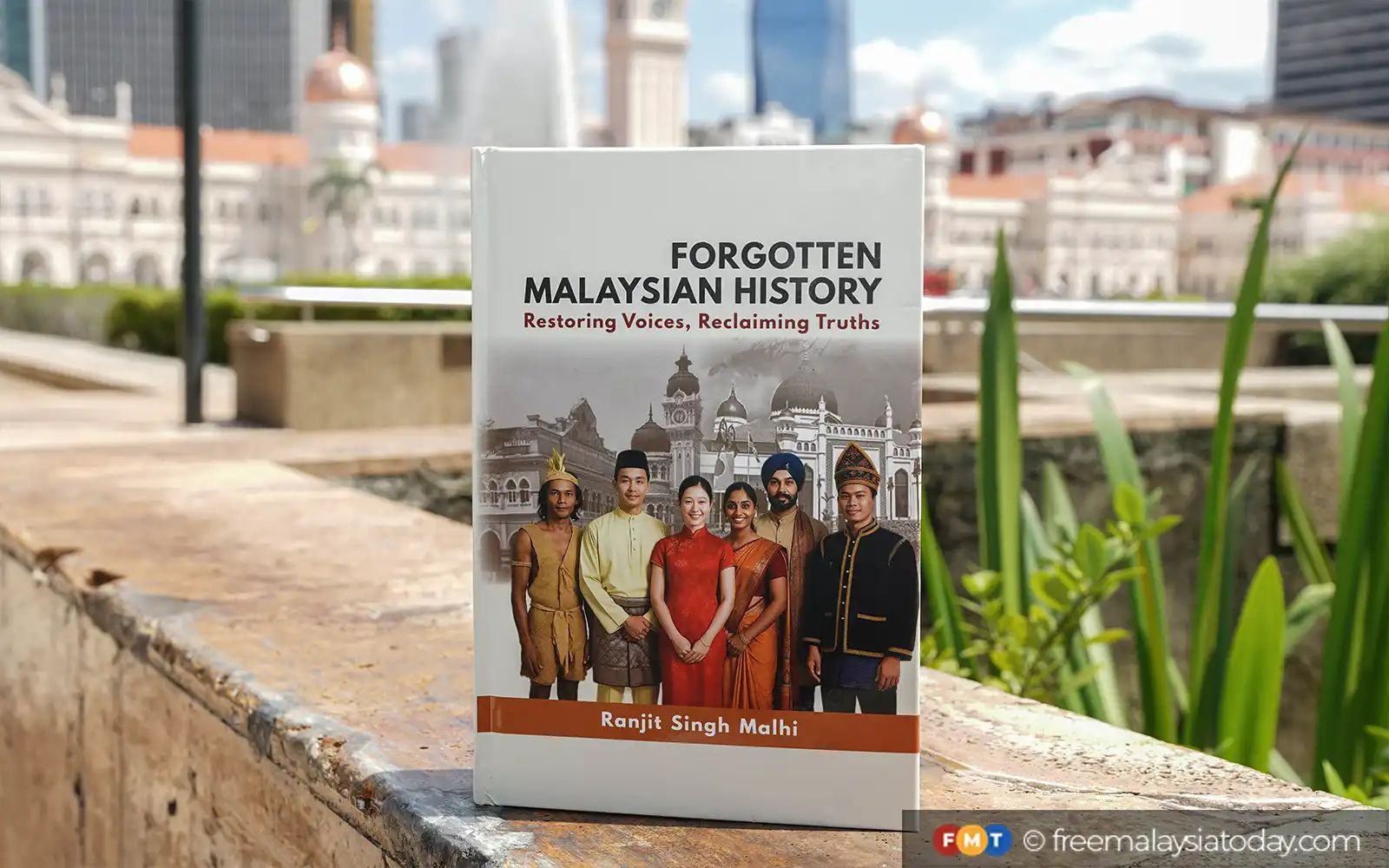

In his new book, Forgotten Malaysian History: Restoring Voices, Reclaiming Truths, Ranjit examines factual distortions found in Malaysian history textbooks.

He explores questions such as whether Penang should be returned to Kedah, the origins of Kuala Lumpur, and the often‑overlooked contributions of Malaysia’s diverse communities towards nation‑building.

A former subject‑matter reviewer appointed by the education ministry from 2002 to 2004 to verify the accuracy of history textbooks, Ranjit said Malaysia’s school texts over the past three decades have increasingly reflected an “ethno‑nationalist agenda”.

He said textbooks from the 1960s and 1970s were more inclusive, even acknowledging the influence of Hindu-Buddhist civilisations on early Malay kingdoms.

This legacy remains evident in Malay customs and language, he explained, pointing out that between 1,000 and 2,000 words in Bahasa Malaysia were derived from Sanskrit, with an estimated 300 to 600 loanwords coming from Tamil.

“All this has been marginalised and pushed aside – forgotten,” he said.

Orang Asli, Yap Ah Loy and Parameswara

Critically, Ranjit notes that the Orang Asli have been excluded from the history textbooks currently used in secondary schools across the country.

“Our history books used to make it very clear that the original inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia were the Orang Asli,” he said.

Appointed consulting professional editor for the higher education ministry’s Modul Hubungan Etnik in 2007, Ranjit said the absence of Orang Asli from textbooks undermines historical accuracy and inclusivity.

He also cited distortions as regards Kuala Lumpur’s origin.

Earlier textbooks, he said, clearly stated that the city was developed as a Chinese township, with figures such as Yap Ah Loy playing a central role.

He said the first Chinese Kapitan was Hiu Siew, and that Kuala Lumpur grew from a settlement established in 1859 at the confluence of the Gombak and Klang rivers.

“Yap Ah Loy came later – in 1868 – as the third Chinese Kapitan of Kuala Lumpur,” he said.

“After the Selangor Civil War in 1866 to 1873 and the fire and flood of 1881, Kuala Lumpur was destroyed. Yap Ah Loy almost single-handedly rebuilt Kuala Lumpur.”

Ranjit said Yap’s role, although clearly stated in earlier textbooks, has been removed from current versions.

He also highlighted how the sacrifices of non-Malays have been sidelined, noting that many Chinese died while serving in the Special Branch during the fight against communism, while hundreds of thousands of South Indians lost their lives building the country’s roads, railways and other infrastructure.

He said claims that Parameswara – the Malay prince from Palembang, Sumatra and founder of the Melaka Sultanate – changed his name to Megat Iskandar Shah following his conversion to Islam, were incorrect, as historical records show them to be two separate persons.

Citing the Ming Shih‑lu, the Ming dynasty’s most authoritative historical source, Ranjit explained that Megat Iskandar Shah was Parameswara’s son who, on Oct 5, 1414, informed Emperor Yung‑lo of his accession as sultan following his father’s death.

“(Our) history textbooks should reflect what truly happened, not what we wish had happened,” he said.